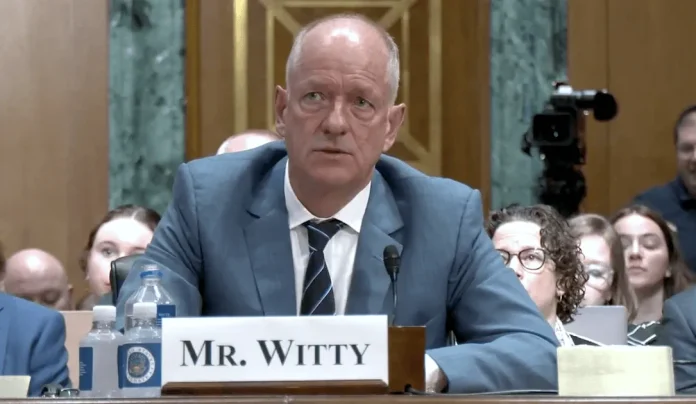

UnitedHealth Group CEO Andrew Witty was battered with questions during a Senate hearing on Wednesday morning about the company’s response to a devastating ransomware attack on Change Healthcare.

Witty confirmed previous reporting for the first time that the company paid a $22 million ransom to the BlackCat/AlphV ransomware gang.

Witty blamed the attack on a server within Change Healthcare’s systems that did not have multifactor authentication enabled and more broadly explained that the company — which UnitedHealth controversially acquired about two years ago — was still undergoing a technology revamp that was moving slower than expected.

Change Healthcare stores patient data both on premises in data centers and also to a limited extent in the cloud, Witty explained.

He was pressed repeatedly on when UnitedHealth would notify the public about how many people had data accessed by the hackers.

In a recent statement, the company said a “substantial proportion of people in America” were affected. Committee chair Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) noted the Justice Department previously found that Change Healthcare maintained data going back to 2012 representing 211 million unique patients.

Witty said determinations on who was affected would take “several weeks,” and that they are working with regulators but could not provide specifics on how that process would be handled.

In a later House subcommittee hearing, Witty said, “maybe a third” of Americans will have data affected by the attack.

“There’s a lot that the American people don’t know,” said Wyden (D-OR). “We don’t even know what data was stolen, and I’m not convinced that we are going to find that out anytime soon… This data can reveal abortions, mental health conditions, sexually transmitted infections and more.”

“I think that your company, on your watch, let the country down and these millions of people, on both the prevention side — with multifactor authentication — and on getting us back and going,” Wyden told Witty.

Wyden added that he has been warned by cybersecurity experts that the widespread ramifications of the incident are “an example to the bad guys of what they can accomplish.”

Restoration concerns

Senators repeatedly disputed Witty’s claims that services had largely been restored, with multiple lawmakers citing specific stories from constituents about having to pay people overtime to comb through the backlog of claims. Witty said he would reach out to senators for specific information to help address the examples raised.

The more than $6 billion in loans provided by UnitedHealth have not been enough to keep some medical organizations afloat, with the backlog of claims amounting to more than $14 billion, according to Sen. Bob Menendez (D-NJ).

Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) said hospitals in her state are dealing with a backlog of nine weeks’ worth of claims, and some facilities are “burdened with a backlog of Medicare claims that is equivalent to 30 days of revenue.”

Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV) noted that healthcare organizations have told her much of the information in the restored systems is inaccurate or missing data, complicating processes further.

Both Wyden and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) hammered Witty over reports that UnitedHealth had used the payment crisis to apply for an emergency order allowing them to acquire a medical practice in Corvallis, Oregon.

Wyden later urged UnitedHealth to commit to creating a “firewall” between the cybersecurity recovery process and the business arm of the company in the hopes that the insurance giant would not use information gleaned from the attack recovery to make future acquisitions and other business decisions. Witty tepidly agreed to the concept but did not provide specifics.

He repeatedly sought to downplay UnitedHealth’s market share when questioned about whether the insurance company — by nature of its size — was a point of failure in the U.S. that hackers could target for maximum benefit.

Multifactor failure

Witty confirmed that as of today all external facing systems at UnitedHealth have two-factor authentication enabled.

When pressed on how UnitedHealth has changed, Witty said the company does scanning of its technology environment and has now “brought external third parties to do double or triple scanning across our systems as a further protection layer.”

“We’ve also made the decision to strengthen our oversight of cybersecurity at the company by bringing it to our board on an every meeting basis,” he said, adding that cybersecurity firm Mandiant has become a board advisor.

“What we saw in Change Healthcare…was an older company [that] had older legacy technologies. But I think it is very typical of many small-to-medium-sized organizations in our healthcare environment. And therefore, inevitably, there’s going to be a lot of work to be done to upgrade those standards.”

Change Healthcare is a “40-year-old company with many different technology generations within it,” he added.

Witty said UnitedHealth was in the process of upgrading and modernizing Change Healthcare’s technology but the attack locked up backup systems that had been developed by Change Healthcare before it was acquired.

“That’s really the root cause of why it’s taken so long to bring it back. We have worked to rebuild a brand new technical environment so that we know it’s modern and not infected by the attack,” he said.

Several senators slammed Witty and UnitedHealth for not having redundant systems that could be turned to in a crisis and for not conducting audits of subsidiaries to identify security lapses.

Future legislation

Multiple lawmakers said the attack on UnitedHealth should prompt a renewed focus on data privacy legislation and minimum standards.

Sen. Thom Tillis (R-N.C.) noted that after the European Union passed its data privacy legislation, there were calls for Congress to also take action that were never heeded.

“We are making a huge mistake by not having federal rules of the road on data privacy data breaches and how these enterprises have to mitigate things, and we’ve really got to work on it because now we’ve got a patchwork of over a dozen states doing it differently,” he said.

“I think it creates distraction and cause for the businesses that take them away from actually protecting our data.”

Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA) added that there should be movement around an effort to create minimum cybersecurity standards — like the incorporation of multifactor authentication — for the entire healthcare industry.