Malicious email attachments with macros are one of the most common ways hackers get in through the door. Huntress security researcher John Hammond discusses how threat hunters can fight back.

Any cybersecurity attack — whether it be a breach, an incident or any form of compromise — starts with hackers getting in through the door. Threat actors and adversaries rely on gaining code execution on a target system which they can then leverage to do more damage—a phase commonly referred to as initial access.

More often than not, the easiest way for an attacker to gain initial access is by exploiting the human vulnerability. This involves tricking an end user into taking some action that ultimately gives the threat actor more power than they had before. They lay a trap and propose a cleverly disguised lie to as many potential victims as possible. Even though a threat actor may attempt to fool a thousand users at one time, they only need one to fall for the charade.

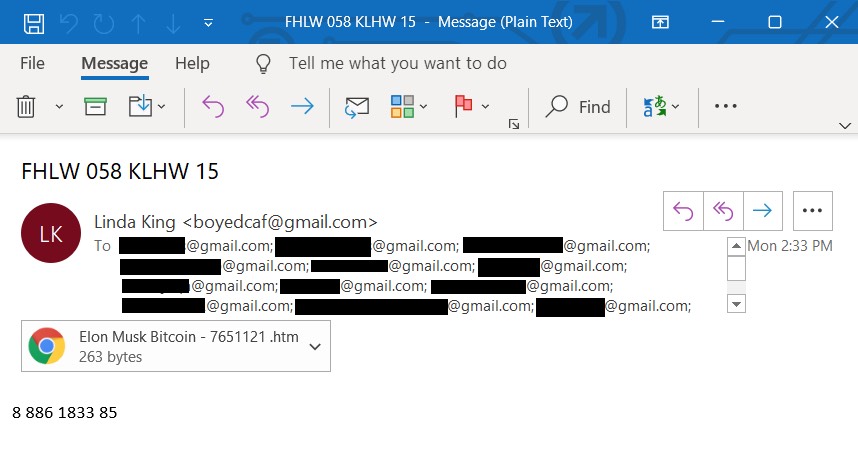

Threat actors design and deliver this scheme typically through email—the easiest way to put digital content in front of any individual. In today’s world, this is common language: “Be careful not to fall for phishing emails.”

For decades, the security industry has attempted to train users to stay vigilant against phishing emails with the boilerplate basics you have heard time and time again: “Look for bad grammar or spelling mistakes,” “double-check the sending address,” “hover over the link,” etc. While these saturated lessons might help ward off the low-hanging fruit, well-crafted phishing emails from sophisticated actors may be genuinely hard to spot.

Bait on the Lure

Phishing emails or any sort of digital deception carry similar traits, but might have different desired outcomes. The most successful phishing campaigns do three things:

- Set the stage with a pretense

- Strike fear with a threat

- Demand action through urgency

Pretense typically tugs at a person’s heartstrings or capitalizes on real-world threats or current events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, taxes or elections, cryptocurrencies, or even blackmail and extortion (“I have your password/I have you on webcam” threats).

The overall goal of a phish, however, varies.

Credential Harvesting

The adversary may set up a “lookalike” website, masquerading as a page that the user expected and intended to go to, but which instead delivers username and password combos to the threat actor when victims attempt to log in.

Session Hijacking

The adversary also may implant code on a staged website or HTML file, forcing the user’s browser to download a file or leave behind cookies that can be used for later actions performed by the threat actor:

Malicious File Attachments

The adversary most often however attaches a specific file to an email, suggesting that the user download it and open it on their own volition. This file often masquerades as a legitimate document, but will instead execute code upon being opened.

Let’s turn our focus to this file-attachment attack vector—specifically, malicious Microsoft Office documents, which can run code with a macro.

Macro Malware

One extremely common file attachment type included in phishing emails are Microsoft Office documents (like Word, PowerPoint or Excel)—masquerading as innocent files that any user or employee might open on a daily basis.

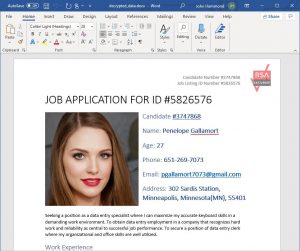

Consider an HR representative or a hiring manager at any company. Their legitimate job function is to receive and handle applications from interested applicants, oftentimes opening incoming emails and downloading their attachments, perhaps to view an incoming prospect’s resume.

Malicious Office documents, or maldocs, can execute code via macros if they are given explicit user permission. Once opened, the adversary must continue the charade and trick the user to click “Enable Editing” or “Enable Content” for a macro to run.

Macro code will execute upon clicking the “Enable Content” via a specific function handler:

Sub Document_Open()

SubstitutePage

End Sub

Sub AutoOpen()

SubstitutePage

End Sub

Sub SubstitutePage()

ActiveDocument.Content.Select

Selection.Delete

ActiveDocument.AttachedTemplate.AutoTextEntries(“Candidate”).Insert Where:=Selection.Range, RichText=True

End Sub

The AutoOpen() or Document_Open() subroutines define the code that will run immediately once the Office document is opened or the user enables content. In the snippet of code above, the process to emulate “decrypting” the content is shown—simply switching out the original document with content that is saved in an attached template, taking advantage of another feature of Microsoft Word to hide things from the user.

Tools of the Trade: Analysis Tactics

There are several tools available to help threat hunters inside companies identify macros and catch them before they detonate. Here are two.

Olevba

This tool tends to be run on Linux as it is a Python tool. It does a nice job of finding key indicators that might set off an alarm for a threat hunter. It generates an output that gives threat researchers a chunk of macro code to see if any of that code warrants additional attention.

ViperMonkey

This tool takes a different approach than Olevba. Whereas Olevba decodes back-end VBAproject.bin files in .ZIP files and generates the source code, ViperMonkey emulates VisualBasic (VB) scripts to a certain extent. It can run VB shellcode and see what it does—all without posing any real harm to users. It can even bypass evasive techniques threat actors take when it comes to malicious Office documents, such as splitting up the code throughout the document to make it harder to identify. ViperMonkey can find those pieces of code and piece them together to be analyzed.

The Perpetual Cyber Battle

Hiding malware within Office documents is not a new trick—it’s just a very successful one. Despite knowing the scams and noticing the red flags, we’re seeing a trend of more targeted and methodical phishing campaigns. And this might leave many defenders feeling like they’re playing a game of whack-a-mole and reacting to the new tricks and tactics that attackers are using. But as attackers have gotten better at social engineering and finding ways to dupe users and their technology, we like to think that us defenders are certainly rising to the challenge and better prepared for battle.

John Hammond is a senior security researcher at Huntress.

Enjoy additional insights from Threatpost’s Infosec Insiders community by visiting our microsite.